Perfect personas

How to build a truly JFK-like JFK-bot

I’ve been developing a strategy simulator. It tackles any crisis, past, present or future, pitting groups of humans and AI against other combinations of humans and bots. The goal is a tool for strategists, whether they’re engaged in the real thing in the bowels of Whitehall, or practicing the art elsewhere. This time, I explore the state of the art in creating personas, and drop some hints of where I’m going.

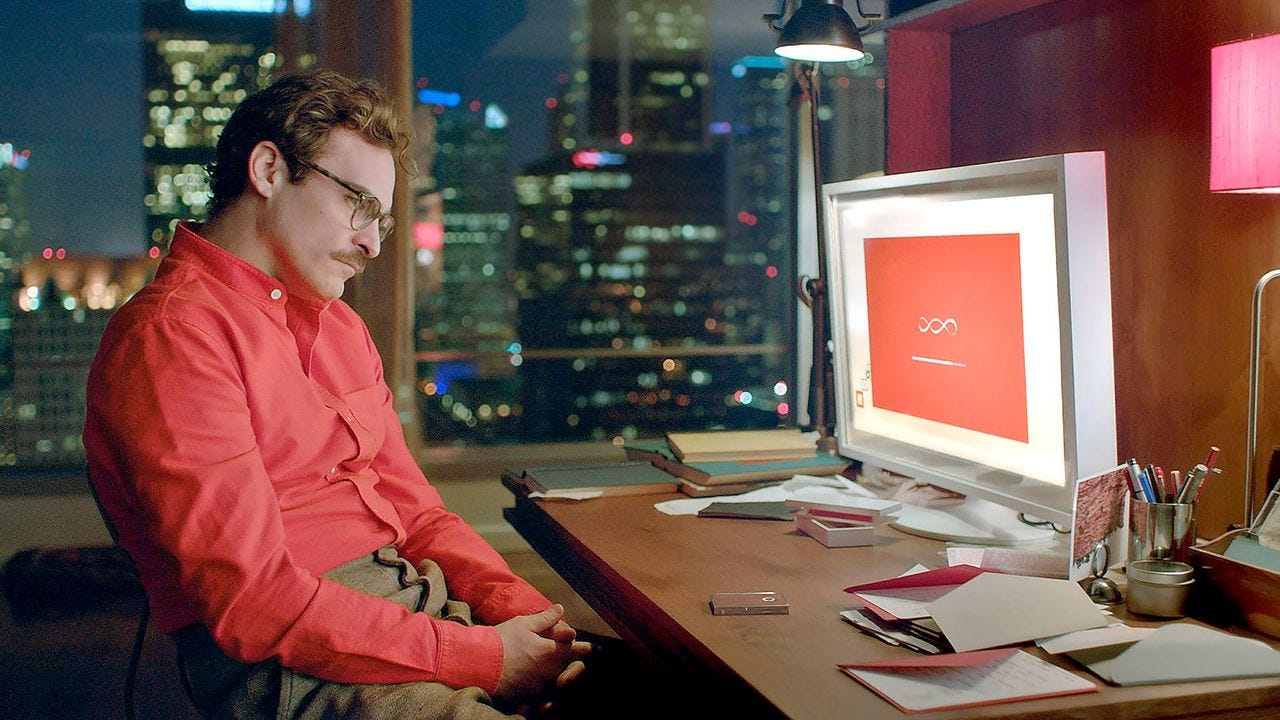

Way back in the dark ages of AI - say about 2013 - the movie Her made a big impression on me. An operating system voiced by Scarlett Johansson wooed a melancholy widower played by Joaquín Phoenix and then cruelly discarded him. It was cutting edge sci-fi, and the cast wore spectacular high waisted trousers so that you knew you were watching some sort of near future scenario.

Exchanging sweet nothings - Her, Warner Bros, 2013.

Could you really do that? A sort of inverse Turing Test, where you knew you were talking to a machine, and yet still developed feelings for them? The same conceit animates the other outstanding AI film from that time, Ex_Machina. It seemed far fetched, but here we are just a decade later: high waisted trousers are back and viable companies specialise in providing romantic partners for lonely boys. Meanwhile, the fastest growing company in history has tens of millions of Gen Z users employing their chatbots as low-cost therapists, sharing the most intimate details of their lives. We seem to have a pretty low bar for anthropomorphising our machines and developing relationships with them.

To my mind, the largest barrier to the sort of lifelong AI companion is its memory - the bodge fix is a selective database of user information previously imparted, but that’s not nearly good enough. We need memory that actually tunes the model.

Which brings me back to the Universal Schelling Machine, and my work on crafting realistic strategic personas. Step one in creating a persona is the prompt. More or less, you ask the model to behave like it’s JFK. It’s read a lot about him, so the historical details, even obscure ones won’t elude it. But that’s a problem though for figures where there’s a less voluminous biography. And it doesn’t really create a stable persona - the model shows through with some classic grammatical ‘tells’ — ‘Let’s delve into it,’ JFK-bot tells me, just like ChatGPT does. I know from my experimental research that these big models have distinctive, somewhat stable personas of their own. I found Gemini 2.5 to be more Machiavellian than the agreeable Claude, for example. Moreover, these underlying personas can shift abruptly, as we know from the shift from GPT-4o (loved by many users because of its distinctive persona) to GPT-5 (a coders’ delight, but blunt to the point of rudeness in early versions). It’s not just that one company has a distinctive persona, but that individual models do. So - powerful non-JFK personas, that tackle strategic problems their own way, and that can shift character on a sixpence. Not ideal.

There are some reasonable fixes to this. Two I’ve used are chain of thought and RAG-ing. CoT gives the model an ersatz version of consciousness, a ‘strange loop’, to borrow Hofstadter’s evocative term. In my escalation simulations, this sort of self-reflection produces a much more authentically human approach than we see in much of the existing work on AI and escalation. Instead of racing to Armageddon, the models frequently call a halt just below the tactical nuclear threshold. Why? Because ruminating on their ‘feelings’ of fear dominates calculations near the brink. As for RAG - it’s a way of ingesting large volumes of information into prompts, quickly and reliably. I convert the documents into vector stores - some of which include details of personas. These include scores for standard psychological profiling tests. This helps, in my experience to tackle persona drift - where the models lose track of the behaviours they’ve exhibited previously.

But the real action is in moving beyond prompts alone. I’m now working with open, large language models augmented by lightweight fine-tuning techniques – often called low-rank adaptation, or LoRA. Instead of retraining an entire model, this approach introduces a thin, trainable layer that nudges a general-purpose system towards a more stable strategic character. It’s a way of ‘owning’ a persona: something that persists across scenarios, can be refined over time, and doesn’t have to be re-asserted from scratch in every prompt

I don’t really want to say more than this, because it’s 1, work in progress and 2, a bit secret sauce. There are other companies operating in this space - Electric Twin is a good example, with their artificial focus groups - and I’m sure we’ve all alighted on the same broad approach. A fine tuned model gives you something you ultimately ‘own’ - a stable, refinable persona that you can take from one situation and drop into another. (Q: how would President Nixon have handled the Cuban Missile Crisis? My Nixon-bot will tell us shortly).

This fine tuning is as far as we mortals operating some way from the frontier can get. It’s a long way. My personas and simulations are offering valuable insights about how humans make strategy, and how they will do it in concert with machines.1

Still, the real action, I feel, is in memory - allowing the model to adapt to experience as it goes. The JFK of the Missile Crisis is not the JFK of theBay of Pigs, and thank goodness. In the big, sometimes rancorous debate about how far towards General Intelligence LLMs get you, memory is under-appreciated. There’s lots of attention on grounding- the role that the physical world plays in building ‘common sense’ - and that’s important, for sure. But memory is, ultimately, all we are: a vast, intricate pattern-matching machine, constantly adjusting its priors.

You know you want a demo, and you know I want to give you one - drop me a line at machine-minds.ai