The ‘Oppenheimer moment’ for AI … is bunkum.

Analogies at war redux

Everyone seems fascinated by the comparison between AI and nuclear weapons. I keep hearing that we are at ‘an Oppenheimer moment’ – capturing the zeitgeist of the film and the sense that this is a vital time. We need, imply those deploying the analogy, some way of controlling AI development – regulating, or perhaps even banning its employment in national security contexts.

I’m unconvinced. Not that AI is as existentially dangerous for the planet – it might be, though I’m sceptical. No, I’m unconvinced that it can be controlled by international agreement in the same way as nuclear weaponry. In short, I think the Oppenheimer analogy is bogus and tells us more about those making it than the reality of the present situation.

Read on…

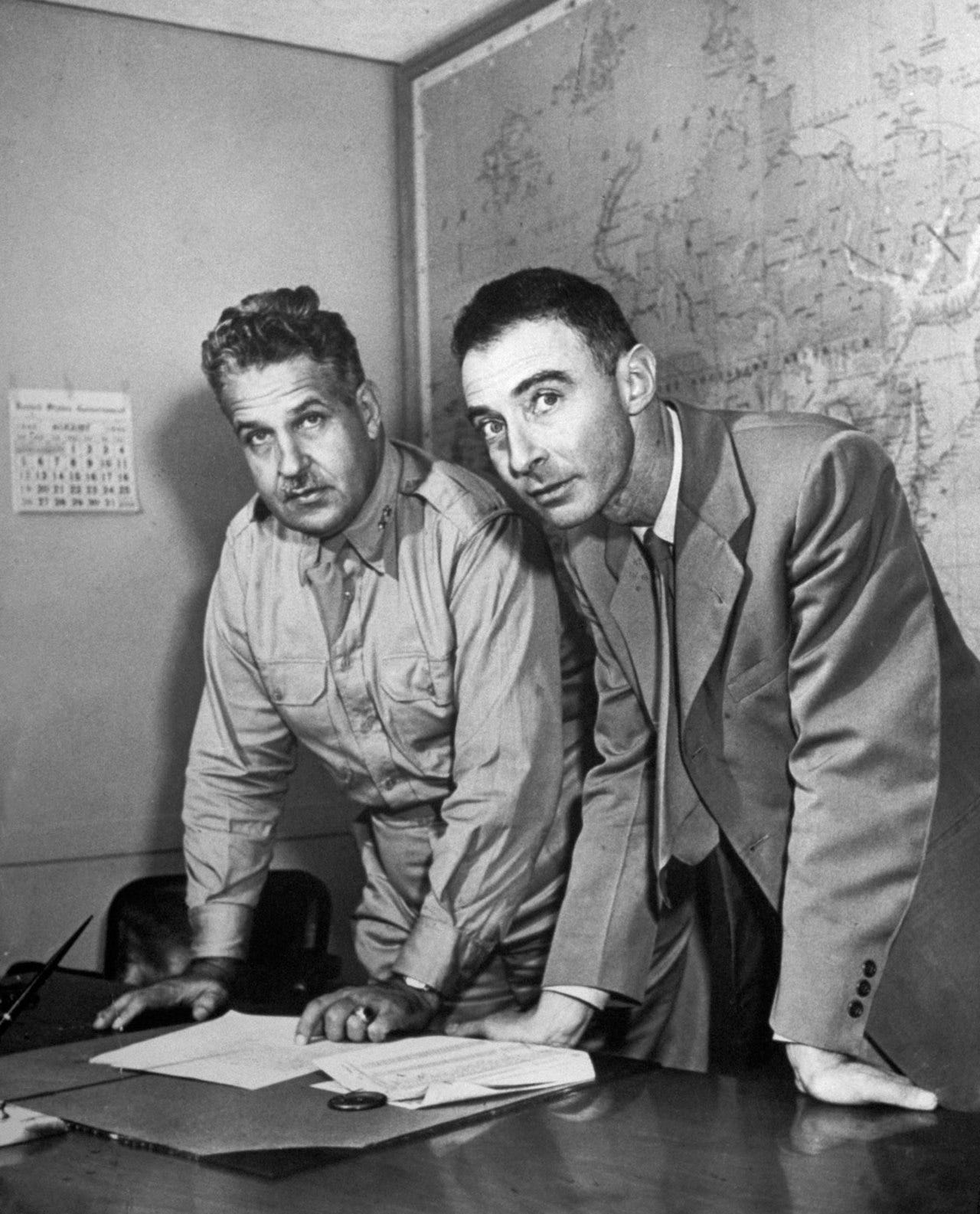

Oppie shares a moment with Leslie Groves, 1942

You can’t beat a bit of analogical reasoning. I learned about it many years ago from Yuen Khong, whose brilliant book Analogies at War is all about the uses and misuses of history by policymakers. LBJ’s foreign policy team – the best and the brightest, remember – were weighing up whether to double down in Vietnam. Yuen looked at their private discussions: analogies abounded.

The problem – the superficial points of similarity between episodes glossed over some profound differences, to the detriment of sound policymaking. Was the Vietnam decision really like Munich in 1938 – the appeasement of a dictator bent on global domination? No. Perhaps, some other advisors wondered, capitulation would be akin to the French defeat at Dien bien Phu: Lack of commitment from the US could prompt an ignominious retreat from the top tier of world power. Again, not really. Or, a third analogy that appealed to some, perhaps the situation was rather like the one America faced in Korean war a decade previously? There were certainly superficial similarities – the Communist invasion of a peninsular in east Asia, and the ‘negative aim’ of defeating the enemy without escalating to thermonuclear war. But there were plenty of differences too – the insurgency in South Vietnam certainly didn’t look much like the conventional warfare Americans faced in Korea.

(Aside: There was another problem for Yuen. Could he be sure all these analogies were instrumental in decisions – or were they reached some other way, with the analogy deployed in support. That’s never really bothered me: To me, it’s far more plausible that an analogy is genuinely constitutive of the worldview of those deploying it – which is why the ‘Oppenheimer moment’ is so interesting.)

And so, back to Oppenheimer. The analogy, as all are, is reductive. Well then, what does it symbolise and what’s stripped out? What does it mean to invoke the Oppenheimer moment?

Firstly, it’s certainly attention grabbing. Oppenheimer-the-movie has given the man himself a renewed place in public conscious. Two years ago, I bet not one person in a hundred had heard of Oppenheimer. No longer. To persuade, analogies must resonate with audiences – and this one clearly has.

Second, the message, loud and clear, is that something big and dangerous is happening. Like the appearance of nuclear weapons, the argument goes, AI has the potential to seriously disrupt existing patterns of geopolitics – perhaps making some states dramatically more powerful than others. I agree. Perhaps there’ll be dramatic changes in strategy, encompassing the ways societies organise themselves for war. Again, I agree. Perhaps there’s even an existential risk for the entirety of humanity. Here, I am sceptical. You can read my arguments elsewhere – but in brief, I think AI changes escalation dynamics; might be offence dominant (contra nuclear weapons); might disrupt the nuclear balance (by threatening assured retaliation); but is unlikely to autonomously bring about general warfare, and lacks intrinsic motivation to deliberately wipe us out on its own account.

Anyway, given points one and two, there’s a call to arms in the ‘Oppenheimer moment’. Those using the analogy are implicitly putting themselves in the shoes of the big man. We can stop this terrible thing, if only we … what? The answer, if made explicit, is usually a call for regulation, sometimes to ban weaponised AI, and sometimes to pause research while we all take a deep breath. It’s here I disagree with the analogistas – none of these things will work because AI is not, when it comes to it, remotely like nuclear weaponry. And, moreover, the analogy, insofar as it holds, points to the failure of concerned scientists to regulate, ban or otherwise tackle the nuclear problem.

Cry baby

Gary Oldman’s President Truman is the best thing in that interminable and dull movie. (I realise I’m in a minority, but how is a movie about something so shocking and awful that melodramatic and tedious?) Anyway, Truman is brutal with our hero, and he’s right. Oppenheimer tells him, ‘I feel there’s blood on my hands’.

On the contrary, revealed Truman: ‘I told him the blood was on my hands — to let me worry about that.’ Oppenheimer is, as Truman bluntly put it, a cry-baby. He wants his cake and to eat it. You can’t be right at centre of developing the bomb and then start bleating about how terrible it is. That’s both painfully obvious, and irrelevant. The bomb, once the physics was known, is a weapon for strategists, not scientists: Truman’s responsibility, not Oppenheimer’s. You don’t invent it to stop fascists and then un-invent it afterwards.

So, campaign against particular types of weapons, by all means. Seek to embed new norms about what’s right. But do so fully in the knowledge that international society is thin and chock full of dangerous people with unpalatable views about how you should live. If you’re a great power, you lose sight of that at your peril. Let’s suppose for a moment that the concerned scientists of the Manhattan Project (and later of Pugwash) had got their way and the US had stepped back from building a nuclear arsenal, or alternatively, had unilaterally placed its stockpile under UN control. Would world peace have ensued? No – only a defenestrated United States squaring off against a nuclear armed Soviet Union.

The unsaid bit of the ‘Oppenheimer moment’ analogy is that he failed. And the failure stems from the same hurdle facing aspirant Oppenheimers today - the security dilemma. If you increase yours, mine necessarily decreases. This isn’t entirely an imaginary, as some would wish. It’s not a social construct that can just be discussed away, or attenuated by the emergence and consolidation of shared norms about what international relations should be like, in some ideal alternative reality. At some irreducible level, we humans live and think in groups. Truman, understanding that, had a surer grasp of international relations than Oppie.

Hans Morgenthau, the arch realist scholar writing in that period, considered the idea world government as the only viable solution to the dangers of the nuclear era. It would, he conceded, be a tough ask. But that’s the challenge facing constructivists today; that we somehow become so enmeshed in the shared values of disarmament that we are essentially part of the same polity: a thick society with plenty of trust. It didn’t happen for Morgenthau in the early nuclear era, and it won’t happen today in the early AI era.

Norms versus realpolitik

Well sure – but what about the rules we do have already – including in the nuclear sphere? Surely these are evidence of the very real power of norms; of the potential for shared global ideas about what is, and is not permissible – even in national security? An ever thickening layer of norms and conventions, embodied in international laws, surely indicates that progress is possible. If nuclear weapons are so vital, why is it that fewer than a dozen states have acquired them? And why have we banned other indiscriminate and cruel weapons by mutual agreement?

There are a range of reasons – aside from the warm glow of our shared humanity. Sometimes, as with chemical weapons, it’s that these weapons aren’t terribly useful, militarily, or can be substituted by others. In other instances, it’s that they are tools for the weak, so that the strong seek to curtail their legitimacy – hence the longstanding (but somewhat tattered) taboo against assassination with poison.

In the case of nuclear weapons, our direct comparison for the ‘Oppenheimer moment’ posse, it’s true that there is an array of effective treaties, outlawing proliferation, testing &etc. And there’s an embedded nuclear taboo – a powerful aversion to their actual use. This, though, isn’t evidence of success. The powerful still have nuclear weapons in abundance, consider them strategically vital and show no signs of giving them up. The norm against nuclear use is irrelevant for gauging how useful they are. Their utility for great powers stems precisely from their non-use, as a deterrent. That’s why they continue to spend vast sums on maintaining and modernising their arsenals. Meanwhile, gaggles of ostensibly non-nuclear states hide under the skirts of larger nuclear armed powers. The arms control regime, such as it is, is primarily designed to stop non-nuclear states joining the top table. That’s power politics in action, not shared values.

The AI-nuclear comparison comes apart

So the track record of regulating nuclear weapons tells us little about their strategic utility. Truman won the debate; Oppie lost. Can it tell us anything about AI today? Perhaps – but not quite the message intended by those deploying the ‘Oppenheimer moment’. We can’t seize the moment with a global arms control regime for AI. As with nuclear weapons, regulating AI will prove incredibly challenging, because the most powerful states likewise consider them strategically vital.

In fact, it’ll prove far, far harder than regulating nuclear weapons. Why? Because many of the restraints on nuclear proliferation and employment don’t hold here. AI differs from nuclear weapons to such a degree the whole edifice of the ‘Oppenheimer moment’ starts to crack under their weight. Let me highlight just two big ones here:

First, defection from any agreed restraints is relatively straightforward and hard to detect. It’s easy to tell when someone is playing by the nuclear rules – and, as Iran, Syria and Iraq discovered, it can be very costly when defection is spotted. Nuclear weapon systems have a large signature: they use scarce materials, require heavy industrial processes that generate large signatures. Much of this is specialised for military use – there’s no civil rationale for enriching uranium or manufacturing nuclear tipped ballistic missiles. AI contrasts starkly. Yes, you need enormous computer power and energy to be right at the frontier. But you can certainly acquire useful military AI without being there. AI isn’t a discrete technology like nuclear weapons – where you either have it, or not. AI is general purpose, with fuzzy boundaries. Repurposing civilian AI for military purposes is inevitable. Even if they aren’t as sophisticated as the US, many states will have the ability to acquire and instrumentalise AI for military employment.

Second, military utility. Nuclear weapons are a powerful deterrent – defending possessors by the threat of punishment. AI, by contrast, offers a much broader array of military possibilities – from back-office logistics, through battlespace management, operational decision-support and on to autonomous weapons. States not only have the means to skirt regulation, but the motive. That’s more so given the huge uncertainty about what AI can do. Might it, for example, boost the offensive power of armed forces? Or greatly boost either the mass or speed of decision-making? Perhaps – and in that perhaps is enough incentive to press on.

So states have both the means and motive to circumvent regulation. And one last bonus reason that the Oppenheimer moment will prove frustrating for those who lean on the analogy: The AI revolution is far from over. Once the theoretical physics had been worked out, what remained for the Manhattan Project was an engineering challenge. Either you achieved fission, or not. Not so for intelligence. It’s a spectrum, not a binary. That makes for a moving target. AI breakthroughs have become routine, and their pace seems to be accelerating. The moment governments think there really is an existential risk from ‘superintelligence’ watch them federalise it, in a heartbeat. Until then, they’ll let the research outfits press on, make the right noises about responsible AI, and risk management. And stay in the race. Yes, ‘race’: the AI arms race is not, I fear, a social construct that we can talk our way out of.

If you’ve made it this far into a long post, you might be wondering why I’m serving as a Commissioner for the Global Commission on responsible AI in the military domain. I’ll expand on that in another post – but the short answer is that I don’t equate ‘responsible’ with international regulation, still less ban.